“All tourists cherish an illusion, of which no amount of experience can ever completely cure them; they imagine that they will find time, in the course of their travels, to do a lot of reading.

They see themselves, at the end of a day’s sight-seeing or motoring, or while they are sitting in the train, studiously turning over the pages of all the vast and serious works which, at ordinary seasons, they never find time to read.

They start for a fortnight’s tour in France, taking with them The Critique of Pure Reason , Appearance and Reality, the complete works of Dante and the Golden Bough.

They come home to make the discovery that they have read something less than half a chapter of the Golden Bough and the first fifty-two lines of the Inferno.

But that does not prevent them from taking just as many books the next time they set out on their travels.”

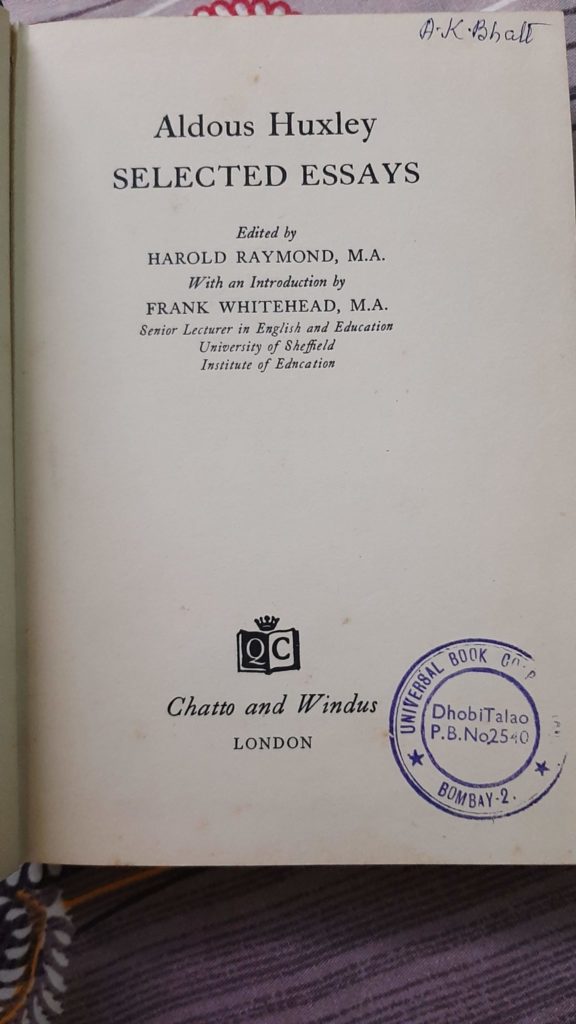

This observation was made by British writer Aldous Huxley in his essay ‘Books for the Journey’.

Here, he talks about the books that one should carry while travelling.

He admits that, ‘along with the books which I know it is possible to read, I still continue to put in a few impossible in the pious hope that someday, somehow, they will get read. Thick tomes have travelled with me for thousands of kilometres across the face of Europe and have returned with their secrets unviolated.’

He says that essential qualities in a good travelling-book are these :

- one can open it anywhere and be sure of finding something interesting, complete in itself and susceptible of being read in a short time.

For example, a good anthology of poetry in which every page contains something complete and perfect in itself.

He likes Edward Thomas’s Pocket Book of Poems and Songs for the Open Air

Another book that he prefers is a collection of maxims (or aphorisms) by La Rochefoucauld.

It takes a minute to read a maxim , and this provides a matter upon which thought can ruminate for an hour.

But, the book that he carries with him whenever he is travelling abroad is a volume of the twelfth edition of Encyclopedia Britannica.

This book is a medium sized book (eight and half inches by six and a half by one).

It contains a thousand pages and lots of curious and improbable facts.

It can be dipped into anywhere, its component chapters are complete in themselves and not too long.

He considers the reading of an Encyclopedia as an activity for amusement.

He explains that we don’t go mad in the process of reading multiple different things in an Encyclopedia because we read it and soon forget about it. Some interesting facts tickles our imagination, and that’s it.

At the end, he talks about our mind’s ability to forget unnecessary things.

He says,

” The mind has a vast capacity for oblivion. Providentially; otherwise, in the chaos of futile memories, it would be impossible to remember anything useful or coherent.

In practice, we work with generalisations, abstracted out of the turmoil or realities.

If we remember everything perfectly, we should never be able to generalise at all; for there would appear before our minds nothing but individual images, precise and different.

Without ignorance we could not generalise.

Let us thank Heaven for our powers of forgetting.

With regard to the Encyclopedia, they are enormous. The mind only remembers that of which it has some need.

Five minutes after reading about mountain spinach , the ordinary man, who is neither a botanist nor a cook, has forgotten all about it.

Read for amusement, the Encyclopedia serves only to distract for the moment; it does not instruct, it deposits nothing on the surface of the mind that will remain.”

Share this:

Cover Image courtesy by Mystic Art Design from Pixabay